By Ingrid Schoon

Professor, University College London Institute of Education

and Anthony Mann

Senior Analyst, OECD Directorate for Education and Skills

In this uncertain world, there is one thing that few economists doubt: the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic will have a serious impact on the employment opportunities of young people. Even before the pandemic struck, youth faced a labour market characterised by temporary and precarious employment, commonly experiencing unemployment rates up to three times higher than adults.

In the months and years ahead, the economic prospects of the young can be expected to become still more difficult – as they did in the aftermath of the global financial collapse of 2008. Analysis of that recession provides important insight into why youth are so vulnerable, but also how some countries were able to buffer the young against the worst consequences of a global economic downturn. By looking back, important lessons emerge for policy makers grappling with challenges lying ahead.

Why are young people so vulnerable during economic downturns?

Employers commonly respond to falling demand by pausing recruitment, decreasing involvement in training programmes such as apprenticeships and reducing staffing through a last-in/first-out policy. The jobs that many young people do are at particularly high risk of automation, and often involve contracts without employment insurance, health benefits or paid leave. Precarious employment conditions and early experiences of unemployment bring with them long-term scarring effects regarding future job prospects, health and well-being.

As society seeks to rebuild after the pandemic, it is essential to take into account the pressing needs of young people to find viable employment and training. Urgent action is required for governments to support young people and future generations as they make the transition from education and training into sustained employment.

What can be done?

Since the 2008 recession, significant work has been undertaken by researchers exploring what governments and education systems can do to protect young people.

The evidence points to three critical measures:

1. Creating strong connections between education institutions and employers

Strong bridges between education systems and labour markets play an important role in buffering the negative effects of economic downturn on young people’s employment prospects. In particular, high quality, high volume vocational education training (VET) has been shown to be effective in facilitating smooth transitions into the labour market and entry into viable careers, including at times of crisis.

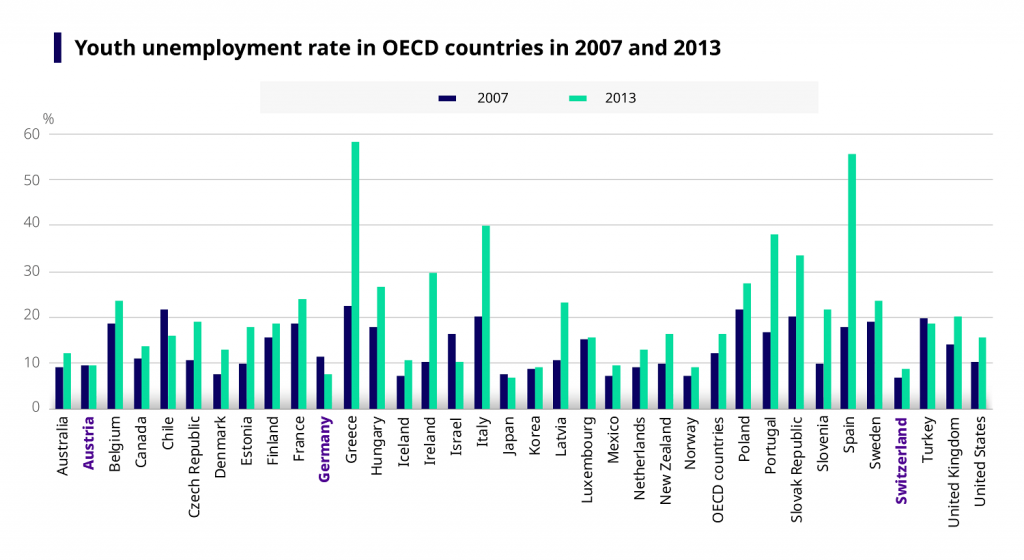

This was the case for example, in German-speaking countries (highlighted in the chart below) following the 2008 recession. In such countries, strong social partnerships help to ensure that the costs to employers and apprentices of apprenticeship programmes are balanced by the benefits they receive. Where the provision of apprenticeships is in the employer’s interest, there is strong likelihood that young people will move into permanent work afterwards. Artificial incentives such as subsidies for employers can distort patterns of labour market demand, engaging young people on programmes with poor long-term prospects.

Government interventions are most valuable if they focus on the quality of apprenticeship provision, the duration, pay and support available to ratchet up the productivity of apprentices. Especially attractive are degree apprenticeships that are developed by employers, universities and professional bodies, and attract high calibre school leavers. More generally, programmes rich in work-based learning give young people the experience, contacts and confidence they need to succeed in tight labour markets.

Post-coronavirus, education systems will have to overcome the likely challenges in engaging employers to deliver work-based learning in a world defined by social distancing. It will be essential to overcome barriers to ensure that young people gain authentic experiences of work as they develop the knowledge and skills demanded by the labour market.

The combination of a strong VET system with strict employment protection has shown to be effective in ensuring a smooth transition and good career prospects by matching skills and knowledge with employer demand. There is thus a case to expand and enforce programmes such as the EU Youth Employment Initiative and to provide sustainable support for the most vulnerable.

2. Providing well-focused career guidance and information for all learners

In 2019, the OECD, Cedefop, European Commission, European Training Foundation, ILO and UNESCO launched a joint leaflet on the importance of career guidance. The publication recognised that with today’s young people staying in education longer than any preceding generation, they need to make ever more decisions about what, where and how hard to study in order to secure the qualifications needed to pursue their aspirations. With work increasingly automated and precarious however, decision-making has become more difficult.

In a recession, the importance of guidance grows. Demand for employment falls, but in an uneven way. Young people, who might have expected to move into work, commonly try to weather the storm by staying in education. Typically, it is lower achieving young people from more disadvantaged backgrounds with weak access to family-based guidance who most need help from career guidance services in making informed decisions.

OECD PISA 2018 data show that young people’s career expectations tend to be unrealistic, poorly informed and distorted by gender, social class and migrant status. A turbulent economy is likely to increase the mismatch between labour market demand and young people’s occupational aspirations and educational qualifications.

The pandemic is an opportunity to broaden the interests of young people, witnessing the contributions that so many (often overlooked) workers make to the fundamental operation of society.

The pandemic however, also represents an opportunity to broaden the interests of young people as they witness in real time the contributions that so many (often overlooked) workers make to the fundamental operation of society and the struggle against the coronavirus. During this crisis, a differentiation has been made between ‘essential’ and ‘non-essential’ work. Essential workers include those in the caring professions, social services, transport and service industries (including cleaners and refuse collectors). Most of these occupations do not score high in social prestige, are generally poorly paid and without sufficient job security. In times of crisis however, we are strongly dependent on them. Making the positive contributions of these ‘essential industries’ more visible could broaden the aspirations of young people. At the same time, the case grows stronger for properly rewarding those employed in ‘essential industries’, providing opportunities for further training and upskilling, and movement up the occupational hierarchy.

Across the OECD, compulsory education ends on average at age 16. PISA 2018 shows however, that by the age of 15, fewer than half of teenagers have spoken with a career counsellor, attended a job fair or undertaken an internship. Part-time teenage working and school-mediated career development activities have been linked to better employment outcomes than would otherwise be expected. In an economic crisis, it becomes more important than ever for schools to give all young people access to information about the labour market and exposure to the world of work. In the current period of social distancing, it is vital that countries find ways, as is happening in Estonia, to ensure that job fairs and even work placements continue. This guidance will actively support young people in their transition into work, help them become critical thinkers and prepare them to compete in tough recruitment exercises.

3. Introducing remedial interventions to help young people after they leave education

Education systems can increase the competitiveness of all young people for available employment, but they cannot make unemployment disappear. Effective systems will put in place active labour market initiatives to support young workers who struggle to find employment. Interventions should include support for lifelong learning using digital tools and online training sites to facilitate upskilling and reskilling among young workers in a changing labour market, and devote attention as well to addressing the housing needs of young people.

By learning the lessons of past crises, governments and education systems can ensure that the workforce of the future starts its journey on the firmest footing possible today.