Today is World Youth Skills Day and this year it’s more important than ever.

From the start of the first lockdown in March 2020, young people’s prospects worsened significantly across many areas of their lives. Alongside challenges to wellbeing, young people were confronted with lost learning at school, colleges and universities, heightened labour market uncertainty, and a potential decline in internships and work experience placements.

While lost learning at primary and secondary level received significant attention, the impact of lost job skills learning and career preparation for young people has been largely missing from the conversation.

In a new report, which will be out on July 21, we shed light on young people’s career readiness and how it might affect their behaviour as they begin navigating an uncertain labour market. The report is part of a large-scale project to track youth employment, learning, career development and wellbeing during the pandemic in the UK and abroad.

How concerned are young people about lost job skills learning?

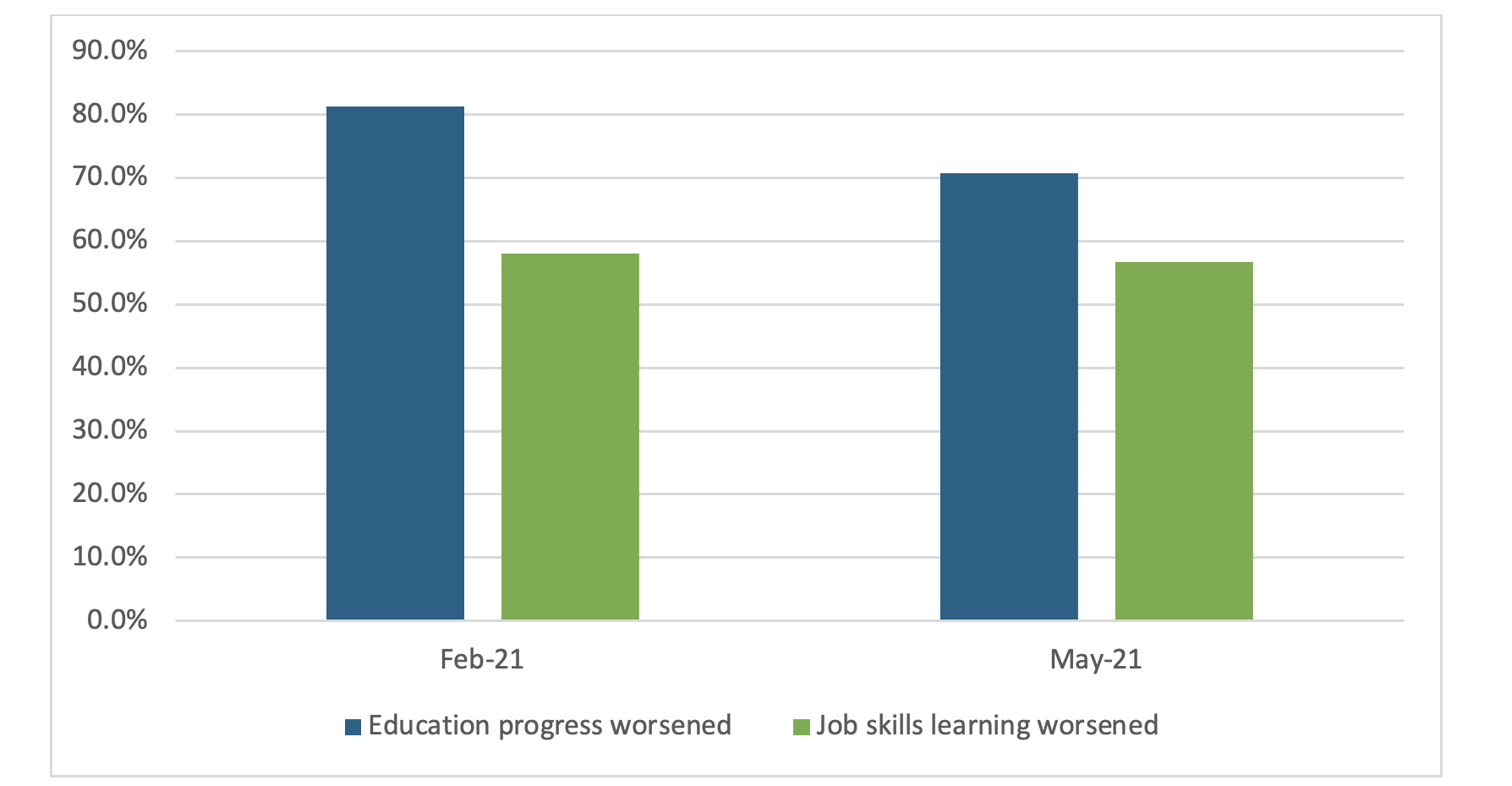

We collected 2,000 voices from a representative sample of young people in Britain aged 16-25 in March and again in May 2021. We asked about their circumstances and the impact the pandemic has had on their lives. About 830 responses came from pupils and students. The chart below displays how young people perceived the pandemic’s impact on their learning progress. It shows the percentages of those who perceived their educational progress to have “worsened a lot” or “worsened a little” during the coronavirus pandemic.

First, in February 2021, the middle of the third national lockdown, 8 in 10 students felt their education progress had worsened due to the pandemic. In May, with schools and colleges re-opening, this fell to 7 in 10.

Second, the majority of students also perceived a worsening of their job skills learning. Although less widespread than concerns about lost education progress, more than half were worried that the pandemic hurt their job skills learning.

Third, unlike worries about education progress, concerns about lost job skills learning did not decline between February and May.

Why should we care?

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is expected to be long lasting: higher levels of youth unemployment now and long-term ‘scarring’ of pay and employment prospects for a whole cohort of young people trying to move from education into employment. One key mechanism through which scarring occurs is the loss of opportunity for young people to acquire job skills in education and immediately after graduation.

Career preparation and, in particular, career-development activities such as internships, work placement or mentorships can help young people to navigate uncertain labour markets. Career preparation can help to shape education and job aspirations and offers opportunities to develop job skills and thus access to good jobs. In so doing, career preparation can boost academic progress and economic outcomes in later life.

How has career preparation held up in the pandemic?

Young people suffered the triple whammy of lost learning time, a sharp drop in available work experience placements and internships, and a switch to remote work and online learning, which might not have been possible for all organisations.

To understand what happened to work experience placements over the pandemic, we looked at the volume of paid working hours among students using the UK Labour Force Survey until March 2021. Not all paid work will strictly support career readiness: in our survey of young people, about a quarter of student jobs directly related to future career aspirations. Nonetheless, besides the direct income loss, changes in the volume of work can indicate trends in work experience placements if the ratio of career-related jobs to career-unrelated jobs remained roughly the same.

The chart displays the volume of hours in paid work for young people in education or training since 2017. For those without a paid job, we set working hours to zero.

Before the pandemic, including the first quarter of 2020, 16 to 25-year-olds in education or training spent on average 6.8 hours per week in paid employment.

The figure has dropped significantly since April 2020. With the country in lockdown in the second quarter of 2020, the volume fell to 4.7 hours per week: a decline of 30 per cent. The third and fourth quarter of 2020, when fewer restrictions were in place and the economy and society opened up, saw some recovery. Still, the volume of work remained below pre-pandemic averages. By the third lockdown in Q1/2021, the volume of paid work among young people in education or training dropped again to about 20 per cent below its pre-pandemic level.

In all, widespread student worries about lost learning of job skills seem justified. Since the first lockdown in March 2020, the volume of paid employment among students has remained significantly below pre-pandemic levels. Our own survey confirms that about one in five students failed to secure an internship despite wanting to do one in the winter and spring of 2021.

Given the potentially significant implication of career preparation for academic and future economic outcomes for young people, addressing learning loss requires a look beyond school performance. It requires that we find ways of helping those on the cusp of entering the labour market and those already entering the labour market.

The government’s Kickstart Scheme seems a step in the right direction. It supports employers to create high-quality work experience placement for young people. Widening eligibility beyond universal credit claimants, enhancing integration with existing career development activities, and extending the scheme beyond its current deadline in December 2021 could help to ensure that more young people who would benefit from job skills learning can access the scheme.

By Golo Henseke and Ingrid Schoon.

Funding for this research is provided by the Economic and Social Research Council. We are grateful for the valuable inputs of our project team: Andy Green, Francis Green, Hao Phan, and Rachel Wilde. The views expressed here are the authors’.

This blog was originally posted on the UCL Institute of Education website.