Andy Green and Neil Kaye

If nothing else, Sunak’s recently announced plan for all students in England to study maths to

age 18 generated a rich crop of maths related puns in the media. Our analysis shows the plan

should be welcomed, at least in principle, as a long-overdue reform – but also how

implementing such a policy without the requisite strategic and financial backing would likely

lead to wider skills gaps and a worsening of the inequalities already seen amongst young people

leaving upper secondary education.

England is amongst a small minority of OECD countries which do not require the study of

either maths or the national language throughout upper secondary education (ages 16-18) (the

others being Australia, New Zealand, Ireland and the other nations in the UK). Furthermore,

less than half of students in post-16 education study maths as a discreet subject, many of them

instead on courses to re-take GCSE maths, in which only a meagre 20 per cent passed at grade

4 or above in 2022. It is no coincidence that literacy and numeracy levels amongst young adults

(age 16-24) in England rank poorly in international surveys of literacy and numeracy skills.

For instance, in the first round of the OECD Survey of Adult Skills (SAS), mean scores for

numeracy were lower amongst 16–24-year-olds in England than in all 22 other countries

included in the survey, bar Italy, Spain and the US. Given the importance of mathematical

competence for undertaking everyday tasks at work and in life generally in our data-rich world,

many school-leavers become particularly disadvantaged by their lack numeracy.

There will certainly be challenges in implementing Sunak’s plans for mandatory maths, as

many critics have been quick to point out. The greatest of these is the shortage of specialist

maths teachers. This would indeed be a major obstacle, particularly in further education

colleges, which cater for the majority of students who lack a good GCSE in maths, and where

maths and numeracy are often taught by non-specialists. The problem is long-standing and

requires a general re-consideration of the pay and working conditions necessary to make

teaching a more attractive profession to graduates.

Critics of the proposal also question whether there is any evidence that compulsory maths

classes would raise numeracy standards. Labour has criticised Sunak’s proposal as a ‘empty

pledge’, with shadow education secretary, Bridgit Phillipson, responding that the ‘prime

minister needs to show his working.’ Kit Yates, director of the Centre for Mathematical

Biology at the University of Bath, writes in the Guardian that compulsion may not be the best

way to encourage more students to study maths and doubts that we have hard evidence that the

policy would work. Such comments beg the question of why students in England should be

considered so uniquely incapable of learning – and benefitting – from maths tuition at upper

secondary level, when their peers in almost all other OECD countries do so, at the same time

scoring better on international surveys of numeracy skills.

In fact, there is substantial research evidence to suggest that compulsory maths to age 18 not

only correlates with higher numeracy levels amongst young adults across countries, but also

contributes to mitigating skills inequalities inherited from lower secondary education (ages 11-

16). Our recent research, for instance, shows that during the upper secondary stage there is a

significant improvement in numeracy skills, as well as reductions in numeracy and literacy

skills inequality, associated with systems where maths (and national language) are compulsory

for students up to the end of upper secondary education (e.g. South Korea, the Czech Republic

and Slovenia).

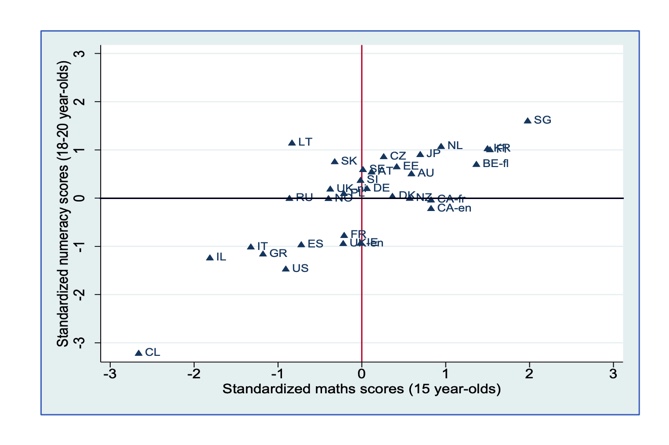

We drew upon OECD survey data from across more than 30 countries and used a quasi-cohort

approach to compare relative outcomes and distributions of core skills amongst 15-year-olds

(using PISA data) and matched cohorts of young people aged 18 to 20 (using Survey of Adult

Skills data). We then assessed the effect of a wide range of education system characteristics on

the levels and inequalities in reading/literacy and maths/numeracy between countries.

Figure 1 shows a strong correlation between average maths scores at age 15 and numeracy

outcomes amongst 18-to-20-year-olds. England (UK-en) is placed in the lower left-hand

quadrant, whereby maths scores are below-average in comparison to other countries already

by age 15 and remain so following completion of upper secondary education.

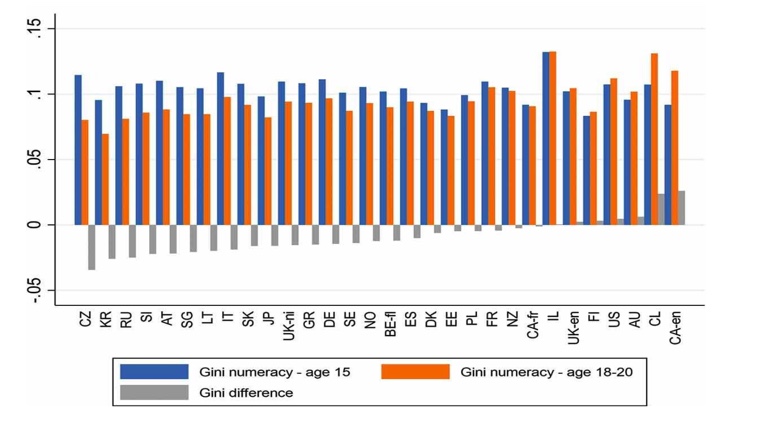

Figure 2 looks more specifically at what happens to skills distributions in maths/numeracy (as

measured using the Gini index) over the upper secondary educational stage. Whilst the majority

of countries included in our analysis are able to close the gap in numeracy during this stage (in

some case, quite considerably, e.g., the Czech Republic (CZ) and South Korea (KR)), there is

almost no change in the distribution of skills in this area in England, similar to other anglophone

countries – Australia (AU), New Zealand (NZ) and the US.

Beyond looking at cross-national trends in skills levels and inequalities, our research examined

how a range of education system characteristics – e.g. curriculum standardisation, ‘parity of

esteem’ between academic and vocational tracks, and teachers’ workload and resources – are combined at upper secondary level, to go some way towards explaining why certain types of

system are more effective in reducing skills gaps than others during this phase. We found that

relatively integrated systems with a substantial degree of standardisation around the length of

programmes and curricula across different programmes (academic and vocational), including

with the mandatory learning of maths and the national language, had significant effects in

raising numeracy levels and reducing numeracy inequality

These findings reinforce those of an earlier study by Green and Pensiero (2018), which found that having compulsory maths and the national language study throughout upper secondary systems was associated with significant improvements in country rankings in skills between age 15 and 27, with rank positions rising by 1.5 places in numeracy (p<.05) and 1.8 (p<0.1) places in literacy. The proportion of students in upper secondary education studying maths (with data taken from Hodgen et al, 2010) also had a significantly effects (P<0.1), increasing country rank positions by 0.64 in literacy and 0.69 in numeracy.

On this basis, we argue that upper secondary education systems might be able to counteract

skills gaps by implementing greater curriculum standardisation across programmes in key areas

relating to core skills learning – especially if that spans academic and vocational programmes.

Nonetheless, we also found that high teacher workloads were also associated with increasing

inequalities in core skills, lending further emphasis to the necessity to recruit and retain greater

numbers of teaching staff if post-16 compulsory maths is to be achievable to any meaningful

degree, and to the benefit of all learners.