By Andy Green

Last week’s report from Alan Milburn’s Social Mobility Commission, Time for a Change, provides a useful assessment of the impact of government policies on social mobility between 1997 and 2017. Ranging over policies for the different phases of education and early working life, it finds that, despite some successes, these have had limited impact in enhancing opportunities for today’s younger generation.

The report concluded that today’s social divisions are not sustainable ‘socially, economically or politically.’ It calls for new ten-year, cross-sectoral targets for social mobility improvements, including a ‘social mobility test’ to be applied to new policies. In my new book, The Crisis for Young People, I have argued for a similar test to judge the effects of policies on intergenerational inequality (which is much the same concept as absolute social mobility).

However, despite the Milburn report’s range, in at least one area – housing – it underestimates the scale of the crisis of opportunities for today’s younger people.

For previous generations, going back until the 1970s, when the late baby boomers came of age, housing proved to be a major source of wealth accumulation and ‘lifestyle mobility’ – if not for all, then at least for a majority. If social mobility were measured in intergenerational changes in consumer power, then housing asset accumulation would have been counted a major engine of mobility both for baby boomers, and for the X Generation (born 1965 to 1979) that followed them. For the Millennial generation, by contrast, the protracted housing crisis has proven to be the major barrier to their life chances, and the main symbol of intergenerational declines in opportunity.

During the seven years preceding the 2008 Crash, the real value of Britain’s private residential housing rose by well over £1.5 trillion – a collective gain in homeowner wealth (even after netting out the costs of home improvements) greater than the UK’s annual GDP at the time. The under 35s owned just 3.2 per cent of Britain’s housing stock, so these increases in property values represented a transfer of wealth of colossal proportions from the future generation of home-buyers to the existing 35 plus generation of home owners. Following the financial crisis there was a drop, but by 2015, prices were again rising so rapidly that many home-owners were earning more (on paper at least) from their homes than from their jobs. According to Government figures in the recent housing White Paper, average house prices in the South East of England rose by £5,000 more than annual average earnings.

Of all the domains in which young people see their opportunities restricted, housing is the most serious, and the one which most clearly represents a growing gap between generations in lifetime opportunities. Housing opportunities are not only declining for an entire generation, they are also becoming more polarised by social class, and more dependent on family background. In terms of home ownership – and the consumption that borrowing against housing assets allows – social mobility is in absolute decline.

Our analysis in the LLAKES Research Centre of the data in the UK Household Longitudinal Study, and its predecessor, The British Household Panel Survey, shows that the proportion of young people aged 18 to 34 in England owning their own homes almost halved between between 1991 and 2013, declining from 46 percent to 25 percent. The decline in home ownership amongst young people affected all socio-economic groups, but it was much greater amongst young people in unskilled, semi-skilled and skilled jobs, than those in professional jobs. Home ownership has also become much more dependent on social background.

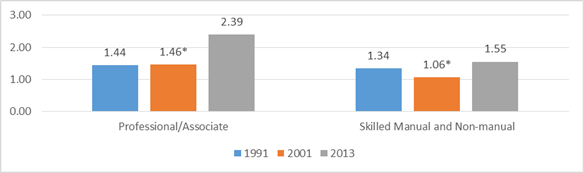

Trends in Odds Ratios for Owning a Home amongst 24 to 34s in England by Parental Occupational Class.

Source: calculations from British Household Panel Survey/UK Household Longitudinal Study data: weighted estimates. The odds ratios are computed cross-sectionally on three waves of the BHPS-UKHLS survey, for years 1991, 2001 and 2013. Note: * means that the estimated odds ratio is not significant at the 95% confidence level.

During the period from 1991 to 2013, the effect of social background on the chances of young people in England owning a home also increased very substantially. The figure above shows the trends in the odds ratios for owning a home for young people with parents in different occupational groups (when the children were 14 years old). In 1991, compared with young people with parents in semi- and unskilled jobs, those with parents in professional and associate professional jobs were 1.44 times as likely to own a home, and those with parents in skilled jobs were 1.34 times as likely. By 2013, those with parents in skilled jobs were now 1.55 times as likely to own a home as those with parents in semi- and unskilled jobs. The increase over time in the odds ratio was even larger for those from more privileged backgrounds. By 2013, young people whose parents had professional jobs were now 2.39 times as likely to own a home as those whose parents had semi- or unskilled jobs.

During a period when the relative benefits of home owning, compared with renting, have never been greater – in terms of quality of tenure, wealth accumulation, and potential consumption power – we have seen inequalities in housing opportunities almost double between children of professional and semi- and unskilled families.

The possibility of owning a home is now increasingly limited to 25 percent of young people who come from better-off families and who inherit or get substantial help with their mortgage deposits from their parents. For the rest the chances of home ownership are very low. For the forseeable future this is likely to remain the biggest source of intergenerational inequality and one of the main challenges for social mobility.

Andy Green’s new book, The Crisis for Young People: Generational Inequalities in Education, Work, Housing and Welfare, It is published today by Palgrave and is available on open access here: